Background

In the early ’50s, when I was about eight, I started lugging around an F Deckel München leaf-shutter viewfinder camera that had been my grandfather’s. Then, driving from Harrisburg PA to Guatemala City before Interstate highways, I started shooting with my Dad’s fancy twin-lens Rolleiflex. It had a flip-up viewfinder enlarger that I loved, which may explain why microscopes and telescopes still intrigue me. Happily, film developing was easy to find and cheap in Mexico and Guatemala, and I still have boxes of prints made from the 2″ X 2″ film, and books full of 35mm negatives, that I collected during the era of CIA skullduggery in Latin America.

My collection of photographic technology took a leap forward when I joined the Navy 12 years later. Assigned to a staff job in the Philippines, I was able to buy a leading-edge single-lens reflex Asahi Pentax Spotmatic II and a bag full of lenses and accessories thanks to cheap prices at the Navy Exchange. Then, after going to Navy flight school in Pensacola, I deployed with my squadron to Vietnam a number of my aircraft photos ended up in the aircraft-carrier USS Constellation’s cruise book (similar to a school year book). I even had some fun with the Spooks in the ship’s Intelligence Center developing and printing aerial shots of a Russian spy ship that I snatched as we flashed past at eye-level.

A few years later, on assignment in Washington DC, I was able to buy some developing and enlarging gear, and began processing and printing in a bathroom at home. Using the toilet seat cover as an enlarger stand, I super-enlarge covert pictures a friend had taken during a Cold War era trip to Russia. Using blow-ups of an off-limits wall map, we discovered and located an unknown Russian space launch facility. About the same time, I became interested in astrophotography, and managed to collect a few photons using a homemade 10″ telescope with a prime-focus adapter for my Pentax. And then digital photography finally reached the consumer market.

My first digital camera was the innovative Nikon 990, a 3Mp two-piece camera with a twist LCD viewfinder, a feature I’ve missed in every camera since. Today I shoot with a fixed-lens Fujifilm X100T viewfinder (my favorite camera ever), a Nikon D50 with a 10.5 mm fisheye, a D90 with an 18-200 zoom and 70-300 Macro, and even an iPhone. Using a Meade LX200 8″ ƒ/7 Schmidt-Cassegrain telescope and image-stacking software I’ve captured the faint light of distant galaxies. Using a conversion ring, I’m again using resurrected Pentax extension tubes and bellows, plus an Apple MacBook Pro portable computer with focus-stacking software for macro-photography. I’ve been delighted by what I find not just in galaxies far, far away, but also right here on Earth and very, very close.

I used iPhoto and then Aperture for image management, but soon moved to Lightroom for post-processing with the help of Nik/Google plugins. With those digital darkroom tools, I’ve created images that have been used by Web sites, newspapers, and magazines including several cover shots, and I won Grand Prize in the 2006 San Diego Air & Space Museum annual photography contest.

My grandfather’s viewfinder camera is in place of honor in the living room, as is my Dad’s Rolli. But I’m still trying to create just the right image.

But Is It Art?

At an 19th century meeting of the Photographic Society of London, one of the members complained that the Daguerre’s new technique was “…too literal to compete with works of art.” Characterized as an artless process that relied on mechanical devices, photography was considered nothing more than, “…a picture painted by the sun without instruction in art,” as Ambrose Bierce put it.

But there were those who disagreed. Elizabeth Barrett Browning loved “…the very shadow of the person lying there fixed forever,” asserting she “…would rather have such a memorial of one I dearly loved, than the noblest artist’s work ever produced not in respect (or disrespect) of art, but for love’s sake.”

However, the view of photography as a mechanical recording medium persisted into the 1960s and even the ’70s, when art photography was found only in niche galleries and minor publications where they were enjoyed by a few aficionados. In fact, analog photography took over 150 years to gain acceptance as a collectable form of art, and it was even longer before digital prints started to appear in a few museums and galleries.

It wasn’t until 2004, when the Getty Museum made their first major digital print acquisition of ”thirteen prints produced on an ink-jet printer” that digital prints were regarded as true photographic art. Today, when such prints are sold, they are not sold merely as digital prints or inkjet prints, but as fine art prints.

In 2011 a photograph by Andreas Gursky’s Rhein II sold for $4,338,500 at Christie’s in New York, a record for any photograph sold at auction. Extraneous details such as people walking their dogs, bicyclists, and a factory were removed using digital editing. Florence Waters, in the London Telegraph, wrote, “…the National Gallery announced their first ever major blockbuster exhibition of photography next year, cementing the art form as a medium of major historic and cultural significance that now even the naysayers can’t deny.“ She went on to say, “…this image shows a great deal of confidence in its effectiveness and potential for creating atmospheric, hyper-real scenarios that in turn teach us to see…the world around us anew. The scale, attention to colour and form…can be read as a deliberate challenge to painting’s status as a higher art form.“

Musicians use synthesizers, movie and TV directors use CGI. Just as rock and chisel, canvas and pigment, clay and oven are artists’ tools; analog cameras, film, and chemicals and now digital cameras, computers, and software are tools that allow human creative skill and imagination to produce works that can equally be appreciated for their beauty and emotional power.

What Makes A Great Photo?

Most people who take pictures know to use the rule of thirds, avoid cutting off peoples feet, keep the horizon straight, and so forth. But if you do all that some pictures still seem crappy, some are nice, and some are pleasing. Why? Are there certain fundamental characteristics that distinguish a stunning professional-quality photo from a boring snapshot? It turns out there are, and you can use those characteristics to improve your photography.

Researchers at Carnegie-Mellon and Microsoft asked professional and amateur photographers, and even non-photographers, to report what they thought made a great photo. Then they put computers to work digging into a mountain of images to mine the best ones. They struck gold when they found that people universally agree on three characteristics that make the difference between good and bad photographs.

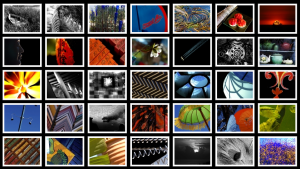

Simple

The single most distinguishing characteristic of top-rated photos in an online photo contest, it turned out, was simplicity. The subject, regardless of what it might be, was easy to separate from the background in good photos while snapshots-quality photos tended to be busy, confusing, and cluttered. A good way to check this is to look at thumbnails. If the little images don’t catch your eye, full size versions probably won’t attract you, either.

The three most common ways to create simplicity are to 1) use a narrow depth of field to blur the background, 2) find lighting contrast—a bright object against a dark background—that will isolate the subject, and 3) use color contrast to make the image pop.

The researchers used edge detection and spatial distribution algorithms on 40,000 contest photos. They found high-rated images had few edges, and poor images had many edges—especially near borders—because of clutter. They also found that the highest rated images appeared more vibrant and colorful, thanks to carefully controlled contrast and brightness.

Surreal

Surprisingly, “real” looking photos were universally considered poor pictures. But if you think about it, that’s exactly what a snapshot is: everyday objects in everyday settings—a simple photographic record of the real world at a particular time and place. What do people like? Surreal was the hands-down favorite, anything that made an image unusual.

Top rated photographers, the researchers found, used lighting and filters to capture a careful selection of unusual but usually complimentary colors or an extraordinary combination of blacks and whites. Good images, they found, are created using special camera settings and positions to create unusual angles and perspectives, and careful post-processing to produce something you won’t see in everyday life. A highly-rated photo was characterized by subject matter that was extraordinary either because the scene, action, or emotion shown was unusual, or because a common subject was captured in an unusual way.

Correct

Photos people liked typically have some part of the photo in sharp focus, although the researchers found that, on average, blur was high.

A zoom lens, pulled during an exposure (such as this image of stained-glass windows by Ken Douglas), can create an interesting blur, and motion blur can be used to show speed—people like that. But a photo with camera shake, or one created with a cheap lens, was seldom appreciated. Good contrast is typical of photographs people like, too. Point and shoot cameras, thanks to cheap lenses, simple sensors that use average brightness, and limited in-camera processing, often produce washed out images that were judged inferior.

All generalization are bad (including this one); likewise every rule has exceptions. We all can point to exceptional images that don’t have these characteristics. But if you make your images simple, surreal and correct, you’ll likely produce images people love.

All images are mine except as noted